Banking and non-banking activities carried on by banks are often closely intertwined and legally difficult to disentangle, especially for systemically important banks (SIBs). Even though SIBs are normally classified as “depository” institutions, a significant portion of their exposures may be non-deposit related—in some instances over 90 percent (e.g., Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley). When SIBs run into trouble and require government support, it will often be because of their nonbanking activities. However, nonbanks, such as hedge funds, asset managers, insurers, pension funds and central counterparties (CCPs), do not overlap with SIBs. Thus, ex ante, there is little economic justification for the argument that those nonbanks should receive taxpayer support, if taxpayer support is justified as protection of deposits.

At the same time, global regulators have already labeled some insurers as systemically important. CCPs have also garnered special status as financial market infrastructures (FMIs) —or financial market utilities (FMUs), as they are termed in the U.S. Despite some earlier arguments that moving over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives to CCPs was not an ideal solution for financial stability, the political reality is that more complex CCPs are here to stay (Singh, 2010). Nonbanks such as CCPs are perhaps the most useful lens to see how regulators rationalize the access of nonbanks to public funds.

This article is based on the premise that it is unlikely that any systemically important CCPs will be allowed to fail. Financial stability considerations will quickly generate pressures for some solution, e.g., supplementary funding such as additional assessments, or access to central bank funds, or haircuts on all users of OTC derivatives etc. Discussions of such matters as a selective or complete tear-up of contracts, bridges (Title II of the Dodd–Frank Act), the portability of contracts to other CCPs and the winding-up of CCPs are not realistic in the OTC derivative space. This is unchartered territory, and the past history of CCP failures and bailouts has not been associated with CCPs that were primarily derivative

CCPs typically do not hold as much “conventional” capital (in the form of equity or equity-like capital instruments) as other financial institutions to provide a loss-absorbing buffer. However due to mandatory clearing, CCPs are now taking on positions in instruments that are less liquid and exposed to less predictable price volatility. As a result the classic tools for managing CCP credit and market risk may not perform as well as they have historically, leaving a residual risk that a CCP may exhaust its waterfall of default resources in managing the failure of a significant clearing member.

We may question, however, what exactly the winding-up of a CCP, or tear-up contracts, or “bridging the defaulting members’ portfolio,” or portability from one CCP to another would look like given the nature of its assets and liabilities. Previous episodes of CCP stress (including the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in 1987), offer little guidance, since those CCPs balance sheets did not have many derivatives. At present, jumps in the derivatives market can have huge impact on CCPs positions, as the “in” and “out” of the money positions are in the trillions of US dollars (BIS, 2014). Requiring all the participants in a CCP (owners/shareholders, clearing members, and end-users) bear the costs will have an impact on other financial entities—i.e., asset managers, pension funds, insurance companies and others. Some argue that this impact on end-users is sufficient to justify the use of public money to rescue CCPs. We think this argument is weak because end-users only are a subset of taxpayers—and the subset can be small or large, depending on the institutional set-up or investment guidelines/regulations of a country.

To the extent that clearing members (CMs) bear the burden of recapitalizing the CCP by absorbing losses and replenishing the default fund, the question arises whether changes to the ownership and governance structure of CCPs are needed. One way to achieve this might be to require user-ownership of CCPs. While some CCPs are currently structured this way, it is not mandated by law, although it has received official support in certain jurisdictions such as the UK, which alludes to “. . . strengthened risk management, fostered by user-ownership and ‘not-for-profit’ arrangements” (Bank of England, 2010). In some cases, CCPs are owned partly by users and partly by for-profit exchanges (for example, LCH Clearnet Limited). In most cases, however, CCPs are owned entirely by exchanges or independent shareholders, and run for profit (for example, ICE). Should CCPs be given a public-interest utility status, becoming entirely user-owned, not-for-profit operations? As discussed earlier, treating CCPs as utilities is not appropriate unless they were to cover the full spectrum of “economic rents” (Singh, 2013).

A default arises when a clearing member (CM) fails to meet a variation margin call in a timely manner. In the absence of the variation margin (VM) payment, the CCP assumes the risk exposure of movements in market prices to non-defaulting clearing members. In that case, the CCP will no longer have a matched book and will be exposed to changes in the market value of its unmatched positions. In order to return to a matched book, the CCP will need to close out its unmatched positions, for example by entering into offsetting/hedging transactions and/or by auctioning the positions to non-defaulting CMs. If market prices move against the CCP during this period the CCP may incur losses. The CCP’s primary protection against this contingent market risk is the initial margin (IM) that it collects from CMs. In case the margin that the CCP holds from the defaulter is not sufficient to meet the loss, the CCP maintains a prefunded default waterfall (i.e., default/guarantee fund) to which all CMs are required to contribute, and is an approximate relation to the amount of risk that each CM brings to the CCP). These funds serve to mutualize the residual loss among the surviving CMs (IMF’s GFSR, 2010). However, waterfalls are not transparent. The recent example of Hanmag Securities, a futures broker in Korea that defaulted in December 2013, is pertinent here. The experience from the Korean clearing house KRX suggests that the fine print matters – KRX capital came after the non-defaulting members’ default fund contributions (SecFin Monitor, 2014).

A further option for loss allocation is haircutting variation margin so that clearing members on the profitable side of market movements (i.e., opposite the loss-making positions held for the defaulting clearing member) do not receive the entirety of the profits expected. From a legal perspective, margin haircutting needs to be limited to VM under existing U.S. and EU laws. EMIR (European Market Infrastructure Regulation) prohibits CCPs from using IM posted by non-defaulting clients/members to cover losses arising from the default of another CM. Also, under proposed Basel III regulations, bank capital requirements will be hard to calculate if there are uncapped liabilities.

Recent ISDA margin surveys and BIS studies suggest that, about US$3.8 trillion of collateral was used as margins (ISDA 2013). Adjusting for double counting of in-the-money and out-of-the-money positions, there is about US$1.9 trillion of collateral that is in-the-money. However, at present, collateral is continuously reused (at least at present by the dealers). Adjusting for a re-use rate of between 2 and 3, collateral that is in in-the-money positions may be in the order of US$700–900 billion (Singh 2013). These estimates are similar on magnitude to the figures reported in the financial statements of the top 10–15 banks active in OTC derivatives market.

However, under-collateralization in this market since Lehman remains in the US$3–5 trillion range (BIS, 2014). As the clearing mandate will result in higher margins under CCPs’ control, there may be sizable funding needs if a CCP is in trouble. The distinction between liquidity needs of a CCP or solvency problems of a CCP is blurred during periods of stress. A variation margin gain haircuts, however, helps to separate the two states. Unlike default waterfalls, VMGH has the effect of funding CCP losses by taking profits from both CMs and indirect participants (or end-users) with positions in-the-money. Since CCPs generally face CMs (and not end-users), CCPs cannot directly haircut the end user. So either there is an agreed 'pass through' of haircut from CM to end-user, in line with the latter’s VM gain positions, or since CM benefits from netting (and collateral reuse) of pooled end-user positions, CM could explicitly commit to assuming all haircuts. Alternately, CMs can charge end-users for this 'insurance' via an ongoing fee.

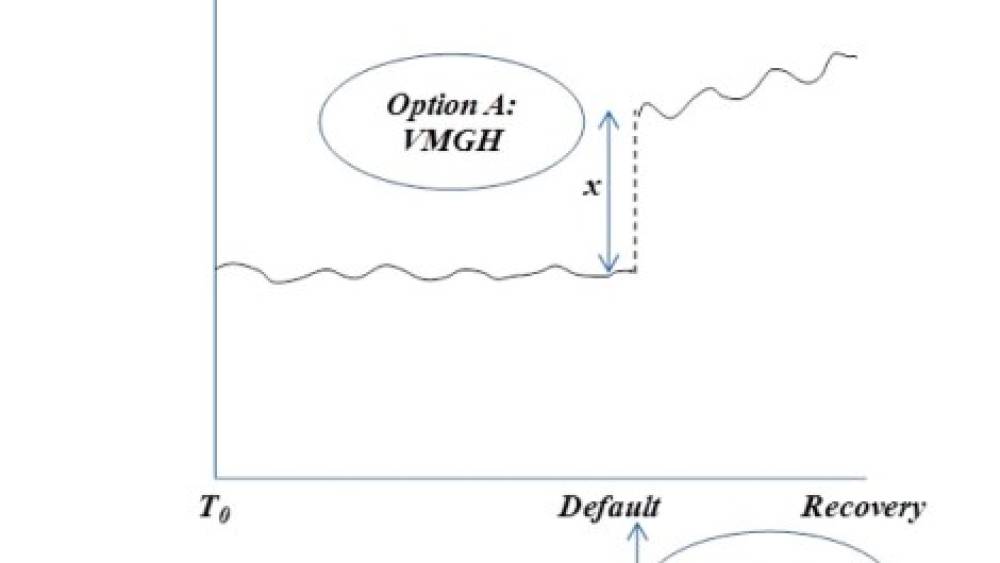

Assume CMs pass on the VMGH to the end user, one way or the other. As an illustration, let’s assume that the positions in a CCP are highly asymmetric, with two big players (an “Asset Manager” like Blackrock with trillions in AUM, and a large hedge fund with $10-15 billion in AUM) that are "in the money" and “out of the money”, respectively, by US$50 billion as a result of a jump event in the OTC derivatives market, while the other n-2 players are neutral to the jump. If the large hedge fund cannot meet the VM stemming from their “out of the money” position to their CM (who in turn has to post to a CCP), then any shortfall x ≤ $50 billion to Blackrock will not be paid; and the hedge fund fails (Figure 1).

The discussion here is about only about x i.e., 0 ≤ x ≤ $50 billion not being paid to Blackrock due to the jump. In other words, if there were a default of a large bank, like Lehman, on a certain day (i.e., the day when the jump takes place), then “in the money” and “out of the money” positions till the previous day would be legally intact, as VMs would have been mostly posted by the end of the previous day. In this illustration, x is a shortfall that could have been modeled to augment the CCP waterfall but this jump event maybe the “the tail of tail risk”. If waterfalls are not robust and not sufficient to cover the jump (due to limited liability of the CCP and the owners), any shortfalls that cannot be met from the waterfall will then likely be “put” to a central bank/Treasury without taking time to ascertain whether the jump has created a temporary liquidity gap in the CCP or whether it has made the CCP insolvent. VMGH provides a sizable cushion that should be sufficient to cover most jump events, or, at least, delay the demand for government/central banks funds. As end-users will have to contribute in a VMGH (unlike the traditional waterfall structures), it is in their best interest to use CCPs with robust waterfall. There are proposals that want to supplement waterfalls (JPMorgan white paper, September 2014). VMGH is thus already forcing all users to look for a market solution.

The VMGH approach is a good proposal to separate the liquidity-versus-solvency ambiguity by providing a concrete measure of unfunded losses and a means of temporarily recouping the losses from non-defaulting in-the-money variation margin payments. It is argued that liquidity support should be available only for solvent, but illiquid CCPs; thus the solvency-versus-liquidity issues are not hard-wired in language. Also, VMGH bridges the gap where liquidity ends and when solvency starts, and thus should not be labeled only as a solvency tool.

Conclusion:

VMGH is not a theoretical possibility. It is a mechanism already embedded in the covenants of several CCPS such as LCH.Clearnet and JSCC. Also, in the U.K., ICE Clear Europe (futures and options), CME’s Clearing Europe, and LME have uncapped VMGH. As VMGH implies wider impact on unfunded losses on default, all participants should take a much greater interest in the governance and risk management of CCPs, protecting against moral hazard, complacency and the cutting corner on risk management for competitive advantage. This setup would reduce the need for central bank liquidity (or government support more generally). Modeling the contagion from defaults by one or more CMs within this new derivatives network is difficult and unchartered territory but some preliminary work suggests VMGH related contagion will be contained (forthcoming, Reserve Bank of Australia paper)